Hurtling through Space

An Educator's Quick Review of a Semester of AI at MIT

Lifelong learning is a good decision.

My SO’s career took us to Cambridge, Massachusetts this past summer. Knowing we were going to move here, I applied to MIT’s Advanced Study Program (ASP).1 The ASP is for local professionals who want to take classes on campus. You’re charged full tuition for the course credit hours, but you receive full credit too. As an ASP student, you are a “non-degree seeking” graduate student. Almost the whole course catalog is open to you so long as you have prior education or work experience that satisfies course prerequisites.

I applied to the ASP, got accepted, and enrolled in 16.413 Principles of Autonomy and Decision Making for the fall semester (see the MIT OCW version of the course to get an idea of the content). What drew me to the course is the systematic study of techniques that I hoped would be applicable to EVA decision support system software like Marvin at work.

Enrolling put me in a unique position in my progression as an educator. My career began with a masters degree in teaching and four years of teaching high school science. It switched directions when I taught myself how to code. And then I was lucky to be able to teach on and contribute to Udacity’s platform, a pedagogical tool that could only exist on the Internet. Going back to a college classroom as a normal student would be a chance to come full circle. I would be a part of the learning process as a student in a traditional classroom, elbow to elbow with classmates in a lecture hall.

Now that the semester is over, I can easily say that I loved the course.

However, my feelings about the course are mostly a reflection of the way I feel about the content itself and the people who put the class together. The professor, Brian Williams, obviously loves what he’s teaching and is a generational expert in the field. He was supported by two TAs, Simon and Sungkweon, who both consistently went above and beyond expectations to help us. I attended multiple office hours sessions where a group of us stayed an extra hour because the two of them were willing to keep answering questions and debugging our code.

I quickly learned that I love autonomy too. It’s the study of general problem solving with code, logic, and math. The techniques are almost universally applicable. Ideas from the course like Markov chains and Bayesian inference are super interesting and useful on their own, and they underpin a lot of the modern work in reinforcement learning. Search, constraint programming, and convex optimization are powerful toolsets for reasoning about real-world systems. I’m already starting to apply techniques from the class in the development of a new prototype EVA decision support system.

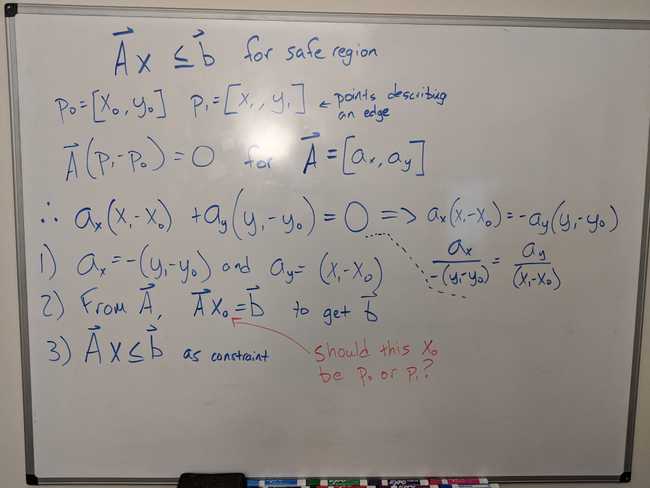

I keep a whiteboard in my office. This is basically how it looked all semester. If you’re curious, what’s shown here is a derivation of linear edge constraints, which just entails determining if a point is on the “safe” side of a line. This was part of my final project of using mixed integer quadratic constraint programming to perform path planning in a two dimensional environment.2 Fun fact, there’s definitely an error here beyond the one I’m asking about in the red marker.

All that being said, I can easily imagine how the “sage on a stage” approach can fall short. There were two 90 minute lectures per week. These lectures were well presented in that all the information you needed was in the slides that were also distributed before class. I rarely took notes during lecture, instead focusing on Prof. Williams’ description of the algorithms and their context within the broader design of decision making systems. Time flew by, and 90 minutes almost felt too short some classes. (Though a few times I drank way too much coffee and felt like I was going to explode out of the lecture hall when class ended.)

But what if the professor isn’t as engaging at Prof. Williams? What if the TAs aren’t answering questions? What if the content just doesn’t grab your attention? What if you just can’t sacrifice the time to commute to campus and sit in a classroom? All of these are reasons that I think platforms like Udacity are so important to make education more accessible to students of all kinds.

Like any good learning experience, this one still required focused self-study. The homework assignments consisted of Python challenges that took us from the simplest of search algorithms through constraint programming and convex optimization solvers. The readings were lengthy, sometimes spanning full chapters in AIMA. I spent upwards of 10 hours a week outside class doing homework, reading, or studying. My Sundays and morning routines were basically dedicated to studying. For the exam, I wasn’t satisfied with breadth or depth of the study material we were given so I wound up assigning myself problems from our various textbooks that reflected what I thought we might see on it.

It’s at this point the parallels to online education resurface. We found that Udacity students fell into two buckets - they either loved or hated the amount of self-study we put on them with questions like “read this documentation and make this thing.” Some thought we were con artists promising to teach them when in reality we told them what they had to teach themselves. But that’s the thing - learning is teaching yourself. A professor can explain things to you, but studies have shown time and again that you have to struggle, analyze, and reason on your own if you want to rewire your brain.

Would I do it again? Absolutely. I already enrolled in the follow up course, 16.412 Cognitive Robotics, with Prof. Williams this spring. So long as MIT keeps letting me in the door, I’m going to keep coming to class.

It’s at this point in the blog post that I wish my experience had given me an aha! moment to unify the benefits of traditional education’s community with online education’s reach, but no. Education is like politics - everyone has an opinion about how it should be done. But unlike politics, everyone is right. We all learn differently. We all need different styles of teaching. We all need different ways of expressing what we learned. We all need to learn in different settings and at our own pace. I don’t want to draw any conclusions, except to say that I hope that companies like Udacity continue to experiment with blended learning. I missed having a real classroom to learn in, but once I got there I realized I missed being able to queue up my studies whenever and however I wanted.

The only real moral to this story is that there is no wrong way to learn. I encourage anyone reading this to make your own lifelong learning a priority in 2020. Happy new year y’all! 🎉

-

MIT isn’t unique in having a professional study program. Many colleges and universities have similar programs under names like “continuing education” or “professional studies.” If this interests you at all, I absolutely recommend perusing the website of a college or university near you to see what they offer. And I especially recommend it if your company gives you an education stipend because these programs aren’t cheap.

↩ -

A good intro to path planning with mixed integer programming: Schouwenaars, T., De Moor, B., Feron, E., & How, J. (2001). Mixed integer programming for multi-vehicle path planning. 2001 European Control Conference, ECC 2001, (March 2014), 2603–2608. https://doi.org/10.23919/ecc.2001.7076321

↩

@misc{Pittman201912A,

author = {Pittman, Cameron},

title = {An educator's quick review of a semester of ai at mit},

journal = {Hurtling through Space},

url = {},

year = {2019},

month = {December},

accessed = {Oct 17, 2022}

}All Rights Reserved, except for the parts enumerated below:

- The source code of this project is covered by the MIT license.

- The content of this project (eg. blog posts) is covered by the CC BY-SA 4.0 license.