Hurtling through Space

From Teacher to AI Researcher

This blog post is both for public consumption and it’s being submitted as my autobiographical essay assignment for 16.990 Leading Creative Teams in Spring 2022. Because I’ve written the autobiography in chronological order with a general philosophy of “show don’t tell”, I’ve included a mapping at the bottom of this post that links the sections of this essay to the major sections required by the assignment.

Last fall, I started graduate school in the MIT Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. I’ve been working on AI/autonomy in the MERS lab. More specifically, I’ve been researching the problem of multi-agent activity planning and scheduling under time delay. These are the class of algorithms used to help robots and humans coordinate their actions when they’re having trouble talking to each other.

I didn’t get accepted to grad school on my first application, or my first admissions cycle for that matter. This was my third application to AeroAstro and fourth application to a grad program at MIT. Since I finished undergrad in 2009, I received a masters in teaching right after college through the New Teacher Project. During and after my teaching career right after college, I applied to grad programs in astronomy and educational technology. There were even a couple applications to graduate programs in scientific writing, with me thinking that I wanted to be a science popularizer like my hero, Carl Sagan. I was accepted to a couple programs and almost enrolled, but I kept bailing at the last second after deciding that I had better opportunities elsewhere. But this time it really happened. This opportunity was too good to pass up.

I applied to AeroAstro because I want my career to define the future of space exploration. Studying astronomy gives you a longer perspective on human events. From the long view, Apollo 11 happened last night. The Wright brothers took flight a few hours before that. We’re at the earliest stages of becoming a multi-planetary species. I want to help us realize our destiny in the solar system.

Knowing myself as an engineer and knowing the kind of problems that pull me and don’t let go, it makes perfect sense that I am where I am now. But from the perspective of my 21 year old self, a teacher with no engineering experience, it seems pretty improbable that I would end up in a career that could impact the long-term direction of space exploration. I haven’t forgotten that I’m a self-taught programmer with no formal engineering education, but here I am doing research and building systems to help people work better in space.

The rest of this post will be an autobiography. I want to start at the beginning of my career after college, when I was a high school teacher with a B- undergrad GPA. I don’t want anyone to read this and think it’s an instruction manual. Unless you’re going into a career with predefined paths like law or medicine, it doesn’t make sense to try to make the same choices as someone and expect the same results. Rather, I want to shed light on who I am now, how I think about the future, and how that shapes my decision making.

Growing up, I could have articulated the same goals about making humans a multi-planetary species without having any idea of how to make them happen. A career was a blank space in my mind, in its place was a vague notion that I wanted to make an impact on humanity's story. I grew up idolizing Carl Sagan and Bill Nye. For a while, I wanted to be a science popularizer. I wanted to be an astronomer. I wanted to be an academic. I wanted to write sci-fi and inspire others. What I really wanted was to be an astronaut, but that dream felt too big to pursue.

I had big dreams and loved science, but I didn’t know what kind of career that would lead me to after college.

Undergrad

My career aspirations failed to fully cement during undergrad at Vanderbilt. I started off as a biology major intending to become an academic in biological sciences, but this was a path I mostly fell into because I took a lot of biology in high school. I considered pursuing a pre-med path, but I never felt enthusiastic about being a doctor. At the beginning of college I was in a work-study program in lab with a zebrafish habitat. As the lowest ranking member of the lab, I spent most of my time performing rote tasks like cleaning tanks and checking pH and salinity levels. This was right around the time that podcasts were becoming really popular. I used to listen to all sorts of science podcasts while I worked, especially anything about space. I kept working in the lab over the summer between my freshman and sophomore years because my family lived just a few minutes away from the Vandy campus in Nashville. That summer, standing between racks of zebrafish, listening to space podcasts and wiping down fish tanks, I had an epiphany that I wanted to switch majors from biology to astronomy. It’s the science I loved most after all, and Vandy had an astronomy department. I figured that even if I couldn’t be an astronaut and go to space, I would at least be happy as a professional astronomer studying space. A few weeks later I met with the head of the astronomy department and changed my major.

I had my first brush with programming in my senior year. I was studying stellar astrophysics, a mixed undergrad/grad level course about how stars work. Our final project was to write code to simulate the conditions inside a star. The final program would amount to iteratively solving seven equations for properties like heat, pressure, density, rate of fusion reactions, etc, at expanding radii and graphing the result. At the time, I had never written a line of code. I had been doing all the math for my homework assignments in Excel. I initially planned on doing the same for the final project, but it quickly became clear that the complexity of the math and the level of accuracy required would make Excel a bad choice.

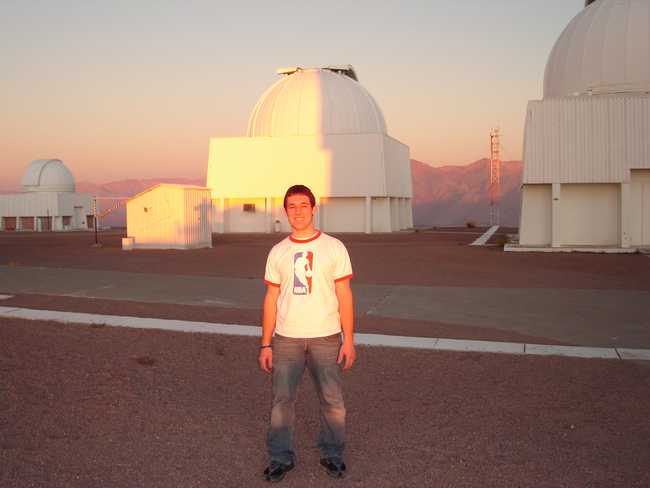

With the telescopes at Cerra Tololo Interamerican Observatory in 2006, where I collected data that eventually turned into my honors thesis.

About a month before the project was due, I decided to switch gears and use an actual programming language for the project. I knew absolutely nothing about programming languages. I picked C++ just because I thought it had a cool name. I spent the next two weeks going through tutorials online to learn enough C++ to do math in loops and write to CSV files. It took me two more weeks to get my project working, but I did (with some help from my prof) and I got an A. I was really proud of that A. In hindsight, maybe this should have been a sign that I ought to take programming more seriously? Learning C++ on your own is no joke, especially as an absolute beginner. I really enjoyed it too. But unfortunately, I wouldn’t open a code editor for almost another five years after I turned in that project.

My experience diving into my first programming language is representative of the strengths that consistently showed up in the assessments we did for LCT. It took courage and a sense of intellectual adventure to go head first into the assignment. This felt like it was tickling a different part of my brain than my physics homework - building something was a wholly different challenge that gave me a chance to exercise creative problem solving skills (also something that I scored highly on in the assessments) in an entirely different way. But I missed the strong signals of my strengths at the time. I was too focused on the challenges at hand (trying to finish my undergrad and be an astronomer) to fully realize how my strengths played into the assignment and what that meant for my career.

When I graduated, I wanted to be an astronomer but I was entirely unprepared to be an academic. I spent so much time in college focused on having as much fun as possible that I missed out on all the obvious preparation for grad school. I barely studied for the GREs. I didn’t attend academic conferences or network with professors. I never even asked my advisor what I would need to do to study astronomy in grad school. Sure I did some undergrad research and collected an honor’s thesis, but that wasn’t enough.

For me, the biggest draw of being an astronomer was that I would have been able to teach. I always loved the idea of teaching college classes and spending my days geeking out over astronomy with students. When the last semester of college rolled around and I realized I wasn’t going to grad school right away, I started considering getting experience teaching high school for a few years and then pursuing a graduate degree later. On the advice of my dad and stepmom, both of whom are school administrators and teacher, I enrolled in The New Teacher Project that spring and started attending job fairs for new teachers. I was offered my first full-time job teaching science at a public high school in Nashville soon after.

Teaching Part 1 - Classroom Management

Teaching was the hardest job I’ve ever had or ever will have. I think most teachers would agree with me, especially anyone who went straight into teaching after college. I’ll never forget the feeling of closing the classroom door behind me for the first time, all alone, as a 22 year old in front of a class of 9th graders. I was suddenly faced with an immense weight of responsibility. I was no longer a dependent of the educational system, I was the educational system. My attitude and my ability to perform, whether good or bad, now had an impact on hundreds of lives besides my own. I was only just learning how to take care of myself as an adult, yet now I was a parental figure for the hundred some odd students that came through my classroom. It was overwhelming.

Then once I reconciled with the level of maturity and self-discipline required to be a good teacher, the lifestyle of the career started to sink in and the story got worse. The pay and the hours didn’t match up, even with summers off. Every morning was an early morning and every night was a late night. My days ended long after the last bell rang. I was stuck on a Sisyphean climb up a mountain of grading. Maybe a handful of times in my teaching career was I lucky enough to leave right after school without creating a backlog of grading and planning I would need to work extra hours later to clear out. There’s basically no such thing as overtime for teachers, making most of those hours spent planning for and chaperoning after school events acts of charity1.

The first challenge I had as a teacher was classroom management. This goes hand in hand with the notion of finding a teaching personality. I didn’t understand my identity yet. I still felt like a student. Was I still a college student, only looking out for myself? Was teaching going to be my career? Was I taking a detour in my career as a scientist? Or was there another career out there for me? I was all of these timelines, shifting between them moment to moment.

The first year was the hardest. I had no classroom management skills. It’s unrealistic to expect that every single student in every single class is engaged, but I struggled to keep enough order such that the students who were eager to learn even could. It was probably the worst kind of crash course a teacher could have, but by the second year I started to understand what mix of classroom rules and teaching persona I could employ to could create a healthy learning environment. In my fourth year I felt like my classroom was finally running like a well-oiled machine.

Two major factors contributed most of the impact to improving my classroom management: (1) I developed a teacher persona that worked for me, and (2) I learned to delegate.

I started off as with a facade of being tough. These students came from rough backgrounds and I was very young and very fresh. I was afraid they would walk all over me if I didn’t seem tough. So I rarely smiled and feigned anger to get their attention. This was a very poor choice.

The students saw right through me. They immediately knew I was fake and hardly listened to a word I said. My classroom was a mess until I learned to use my true personality to shape my appearance in the classroom. In reality, I’m a nerd. I geek out about science and love making jokes. I found a balance somewhere in the middle. My teaching persona was my true persona, just with a stronger emphasis at making and upholding the rules of my classroom. Students responded well, and life in my classroom became a lot saner.

The second emphasis, delegation, took work off my plate and created more engagement with the students. I heard a phrase that “a teacher should never do work a student could do for them,” the idea being that students should take ownership of their learning spaces, with teachers there to facilitate and guide. I took this to heart. I learned that students enjoyed the millions of little tasks it takes to setup for class every day. They’ll happily clean, organize, pass out papers, collect papers, grade each other (not for anything serious), decorate, plan, and otherwise keep the classroom running. My goal turned into doing as little work as possible while my classroom ran itself. It gave me time to focus on the important things, like designing lessons and addressing individual student needs.

The New Teacher Project, much like Teach for America, included a masters in education, which was required for the teaching certification. Ours was administered through Belmont University. Our first classes served as venting sessions. We met after school on Mondays and Wednesday. Our professors let us spend most of our time talking about the struggles we faced. My favorite part was the pre-class venting sessions we had over sushi, burgers, and drinks at the restaurants near campus.

Teaching was more rewarding than anything else I have ever done. All the struggle and sleep deprivation were worth it because I got paid to do what I loved - geeking out with students about science. I was explicit that my goal wasn’t to turn all of my students into professional scientists (though it has been gratifying to see that a few of them have!) - I just wanted my students to enjoy science! Maybe then science would feel accessible. At the very least, making the world a little more understandable makes it a better place.

I found that my best teaching persona is just being myself. At some point in that first year of teaching, I started opening every class with the Astronomy Picture of the Day (APOD). Students would walk in to my classroom with the lights off and the projector on. The first five or ten minutes would consist of a discussion about some neat astronomy image. No quizzes, no grades. Just a moment to relax and appreciate science. Each year usually started off where I would be the only one talking about each image, but by the second semester, the students learned enough that it was usually a group discussion. A few classes got bored of APOD so they asked for something different. I wound up doing the Animal Picture of the Day a few times (not a website, just me finding weird animals on Wikipedia) and sometimes we just talked about science stories in the news.

Whole class lectures were fine, but I mostly enjoyed the small group moments. I loved picking apart the preconceptions students held about the way the world works in order to help them reassemble a more accurate picture. An intuition about science can make all the difference. Of course the math and equations are the ultimate source of truth, but students need robust mental models to guide their thinking.

Labs and hands on learning were my favorite. Nothing beats getting dirty and collecting numbers. Physics teachers tend to get creative about their labs. I enjoyed taking taking classes outside as much as possible. Football fields are great for running physics experiments. We did egg drops off the stands and speed of sound tests across the field. We went to a playground once to talk about conservation of energy while swinging and climbing on the monkey bars. My students took over the school hallways with catapults and race courses for matchbox cars. I helped design an interdisciplinary science class where the students buried dead chickens to learn about forensic science. We took students to water and sewage treatment plants to learn about water chemistry. We went to an observatory to learn about solar physics. One year we were lucky to have a partnership with a nearby university and our students got to do chemistry in their labs.

In the words of Ms. Frizzle, I “got messy” a few times too. And by that I mean I injured myself doing science.

My teaching idol.

I taught freshman physical science2 in my first year of teaching. Students were learning about chemical reactions involving acids and bases, so I wanted to start class with this fun demonstration where you drop a small strip of magnesium in a test tube with hydrochloric acid and it produces hydrogen gas. If you hold another test tube upside down over the reaction (or a balloon), you can capture the hydrogen gas and ignite it, producing a neat “whoop!” sound with a quick flame (I took every opportunity to burn things in my chemistry classes).

As this was my first year of teaching, my knowledge of the chemistry supply closet was incomplete so I asked the other chemistry teacher to help me grab the hydrochloric acid. He handed me a glass bottle and neglected to tell me that it was our concentrated 12 M hydrochloric acid, and, being in a hurry because everything was always crazy that first year, I neglected to ask about the concentration.

At high concentrations under STP, hydrochloric acid visibly off-gases enough that it looks like a witches brew. I don’t know how I didn’t have an alarm in my head blaring 🚨STOP YOU IDIOT THIS IS DANGEROUS🚨 when I poured a few milliliters into a test tube and saw vapors forming. I must have been distracted by my usual classroom management issues. So there I was, standing behind a lab bench in front of a class of freshmen with hydrochloric acid vapors swirling under my face. I had just dropped the magnesium into the test tube when I was seized with an awful burning sensation in my chest. I was drowning in fire. I started heaving and coughing, and of course I dropped the glass test tube, which shattered and sent even more hydrochloric acid vapors into the air. I thought I was dying. I didn’t even realize what had happened at first. I turned my head up trying to get away from whatever evil was tearing through my lungs.

My students were understandably alarmed. My classroom management skills were so bad at that point that, to be honest, I had doubts that my students actually cared about me as a human being. I caught enough breath to start sputtering the name of the other chemistry teacher and the word “clinic.” To my surprise, the two students closest to the door rushed out and got both of them, while the rest backed their desks as far away from me as they could.

A few moments later the front of my classroom was covered in baking soda and I was breathing again. My chest ached. I already sounded hoarse. The nurse said I was probably fine but I should go see a doctor. I gathered all my students back and calmed them down. I was fine, I told them. What had just happened was scary, to be sure, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try the demonstration again. The other chemistry teacher diluted the hydrochloric acid for me, and, eager to not let a small setback like acid burned lungs prevent science from happening, I dissolved some magnesium and blew up the resulting hydrogen gas. I remember my students asking me “why are you trying it again!?” after the whole ordeal, which was a very reasonable question. I told them that mistakes are a great way to learn. You shouldn’t let getting something wrong the first time dissuade you from improving and trying again.

As soon as that class was over, a substitute teacher took over for me and I drove straight to my doctor’s office.

I had my first brush with grad school rejections in my second year of teaching. Life was hard as a new teacher. I still dreamt of life as an astronomer. Nothing had changed about the quality of my applications since I graduated - I knew nothing about the networking and preparation required for grad school. I fired off applications to seven or so schools in a shotgun approach and got rejected from all of them. On a whim, I even sent an application to the MIT Graduate Program in Science Writing. I still had dreams of becoming the next Carl Sagan. I thought I might have a chance because I had a really high GRE writing score and a lot of experience writing about science for my classes (I had just finished writing a 30-page mini textbook on astronomy for one of my interdisciplinary science classes). Of course, this application also got rejected. This would not be the last rejection letter I’d get from MIT.

This felt like a low point. My big plans for a delayed start as an astronomy grad student completely collapsed. I had no idea what to do next. I was starting to love teaching but I still couldn’t quite imagine being a teacher for the rest of my life. I wanted new problems to solve and new skills to learn. I started thinking about starting fresh in another career, like maybe the military. But underneath all that frustration and disappointment was a sense of freedom too. I could be whatever I wanted to be. I had no real responsibilities outside work. No strings, no expectations. I could wing it and see where that led. I soon got the chance.

Teaching Part 2 - Thinking with Portals

A few months later, between my second and third years of teaching, I realized I had a problem with my physics labs. I had the luxury of teaching a class without a standardized exam, which meant I had more freedom in the topics we covered. I liked being able to react to student interest. The school had a small budget for lab equipment and the ordering process took almost a whole school year. As such, I often felt frustrated that I didn’t have the supplies for all the labs I wanted when I wanted them. I had some success getting creative cobbling together labs from the equipment I could find, and sometimes I spent my own money to buy the equipment I needed, but I knew we could do better. What I really needed was time to requisition a closet full of physics equipment. Given it wasn’t going to appear overnight, I started to think of alternatives.

A physics simulator came to mind first. Assuming everyone in the class had access to a half-decent computer, virtual labs in a simulator could be cheap, easy, and flexible. Physlet-style apps had come in handy for a number of lessons. My favorites came from Colorado University’s PhET. The problem with them is that they’re all generally made to demonstrate a single concept. I wanted a general purpose simulator. I play a lot of video games. I realized that cheap and readily available video game physics engines had potential to be the flexible physics lab tool I needed. It wasn’t long until I landed on Portal as my physics lab environment of choice. In Portal, players explicitly solve physics puzzles and the game has a general science-y motif.

A demo of Portal.

I needed a proof of concept lesson. I spent the next few days poring over the levels in Portal, looking for any environments that could be turned into a kinematics lab. I recognized that the tiles in the game were going to be the key to making the labs work. If you watch the trailer above, you’ll see that each room is generally covered in square tiles. Being a standard size and shape, they make for a perfect unit of distance. That opened up a whole range of experiments in kinematics and mechanics.

At the same time, I needed to prove to myself that Portal’s Source Engine mirrored real-world physics well enough to be useful. The physics didn’t need to be perfect, just internally consistent and modeled close enough to real physics to be recognizable. I started running my own experiments. Remember, I had no idea how to code yet. I didn’t know how to open the game console and run commands to pull measurements. Rather, I took the physicist approach. I staged experiments in the game, recorded videos, and used physics tracking software to analyze the motion of cubes. I tracked them falling, sliding, and colliding. Lo and behold, the Source Engine modeled realistic-ish physics.

I sketched out my first unit of lesson plans about projectile motion. In it, I assumed that every student would have a laptop and a copy of the game to play independently. We had a cart of laptops at the school that met Portal’s minimum system requirements, so I wasn’t worried about that. But there was the other issue of getting enough copies of Portal for a whole class. I had an idea to ask the Internet for help. Valve Software, the makers of Portal, frequently gave out free copies of the game. I bet that a bunch of gamers out there had an extra copy of Portal sitting around and maybe, I hoped, they would be willing to donate them to my class. I shared my lesson on reddit (on r/portal and r/gaming) and asked for game donations.

My plan worked. I netted about 20 copies of Portal over the next few days. And then, to my surprise, I found this message in my reddit inbox.

Title: hi from Valve

I just saw your post about using Portal in your physics class, and we’d love to help you out. We’re actually investigating facilitating exactly this with Portal 2, and we’d love to talk about what you’re doing and what you’d like to do.

Email me at [name redacted]@valvesoftware.com, please, and we’ll talk.

I idolized Valve Software. The Half-Life series, the Portal series, Counter-Strike, and Team Fortress 2 were some of my all-time favorite games. When I got an email from an employee there, it felt like a celebrity wanted to meet me. I couldn’t believe it. It felt like validation that I found a problem to solve that other people cared about. I emailed them immediately and that started a relationship that would fundamentally alter the arc of my career.

With hindsight, it’s easy to ascribe meaning to small events like this. Now, ten years later, I can make grandiose claims like “fundamentally alter the arc of my career” because I can clearly trace the cause and effect relationships between the series of events between this one and where I am now. But the truth is that at the time I had no idea what this meant or what was going to happen. I was just excited to see where it led. I remember thinking that it could be something big or it could be nothing at all. And I was okay with that. I used to go on runs after work in the West End neighborhood of Nashville where I lived. The quiet little voice in the back of my head wasn’t so quiet. It was a record on repeat telling me that I could be whatever I wanted to be. The mantra had a weird intonation though. I can’t describe it other than to say it emphasized that future. I had heard this phrase so many times growing up. My loving and supportive parents always told me so. My teachers told me so. But I think this might have been the first moment in my adult life where the idea of a self-deterministic future took hold in with full effect. I saw a life ahead of me. I saw hard work. I saw goals being accomplished. It was all the timelines of all the futures I could have all at once. It’s a great feeling being young and seeing your whole life in front of you. Even though I won’t be young forever, I hope I never lose it.

Back to the story at hand, this one email I got from Valve meant I already came out ahead in the Portal experiment.

After a few back-and-forths, I was put in touch with Valve’s new director of education, Leslie Redd. The first thing that Leslie told me was that Valve could hook up my class with as many copies of the game we needed, but the catch was they wanted me to use the newly released Portal 2 instead. This wasn’t really a catch because Portal 2 included a an easy-to-use level editor. It would be a huge upgrade to my lessons, which I had originally discounted because Portal 2 was a new, full-price game. I began writing a series of lesson plans that would take advantage of the Portal 2 level editor. The level editor would let me reframe my lessons from “find cool physics in Portal to study” to “build physics experiments in Portal and predict the results.” I wrote lessons where students would build contraptions and take measurements in the game world. This would let me task my students with challenges like determining exactly when and by how much the physics in the game diverged from real-life physics (ignoring the fact that portals don’t exist of course).

Demonstrating the use of the Portal 2 level editor in the fall of 2012, a year after my first contact with Valve. Credit: Jeff Unay

In these first conversations with Leslie I learned that Valve wanted to support educators but they didn’t know how to do it. They were excited to meet teachers like me who might be able to foster learning communities around their games. I learned that they had a new website in the works called Teach with Portals (teachwithportals.com seems to have been given over to a group called foundry10 I’m not familiar with, but they’re still hosting my physics lessons!). They wanted teachers to share lesson plans that starred Valve games. I loved it. I was super proud to be a part of the effort to make video games a more mainstream teaching tool.

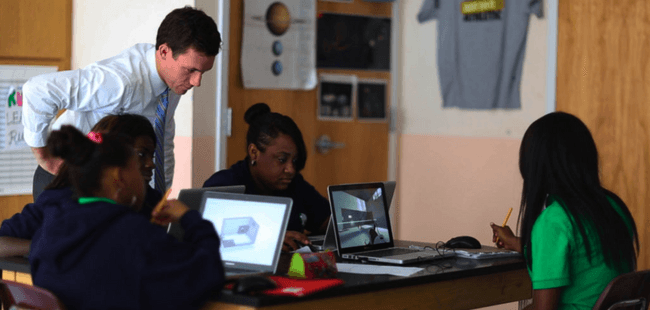

My classroom in the fall of 2012. I’m with some of my 11th grade physics students working on their experiments in Portal 2. Credit: Jeff Unay

Valve’s grand vision for education needed teacher evangelists with a ton of energy and creativity. I recognized an opportunity. They needed me. So, six months after making contact with Valve I drafted this email.

Hi Leslie,

I hope you had a fantastic holiday season. I used my time away from work to gain some perspective on my career and the trajectory I think it should take. I came to the conclusion that I’d like to pursue a career with Valve.

If Valve is serious about education, it will need people with an intuitive understanding of the way education, physics, and video games should interact and interplay. In light of my background in physics and education, I would be a leading asset in not only designing the next generation of virtual physics simulators, but also in promoting and distributing these simulators to educators. After almost three years of teaching, I know what teachers need to improve student learning. I understand the importance of feasible and effective classroom tools. I know how to maximize classroom resources to fit any grade level and ability. Having grown up in a family of educators, I am aware of the type of initiatives school districts are willing to support. I also speak the language of education, which allows me to successfully communicate and sell the utility of tools like the Portal 2 Puzzle Creator to educators.

[A few more paragraphs on what I would do at Valve and my goals for the effort]

Thank you Leslie! I really appreciate the opportunity to be involved in this exciting project. My experience with Valve so far has been nothing less than stellar, especially as a long time fan of your games. I hope my relationship with Valve is only beginning.

Sincerely,

Cameron

It’s hard to know for sure, but I think this was the first time that I took a long view on my choices at hand. I spent a week with this letter, tweaking every word and debating whether or not I should send it. I wasn’t worried so much about being rejected, I was just anxious about putting myself out there. I meant every word in that letter. What if I read the situation wrong and got embarrassed by this whole episode?

I used to go on runs after school through my neighborhood in Nashville. I always daydream when I run. Two scenes kept recurring during those Nashville runs. In one, I imagined picking up a newspaper and reading that a newly selected astronaut started off their career as a high school teacher. To my surprise, it sounded possible. In the other scene, I imagined myself as a 90 year old man sitting in a rocking chair. 90 year old me would be reminiscing about their life and me now at this exact moment. What were they feeling? Was it regret? Disappointment? Pride? The answer was obvious. I sent the letter.

I got a response from Leslie a few days later (I’ve been searching for that email but I think it’s gone - I must have sent the letter with my school email address that I lost access to years ago). She said she agreed with me, and although a full-time job wasn’t possible, Valve could start covering my time spent on lesson plans and such as a part-time consultant. Looking back, it’s weird that I don’t remember the moment of receiving Leslie’s email very well. I was so nervous and stressed. I was initially disappointed about full-time but I came to realize that this was still a tremendous success. Here I was, some nobody teacher, heads down in their classroom, and I found a way to claw up and out to the bigger world outside with a group of people that mattered.

Valve sent me a portal gun signed by Valve founder and Internet celebrity Gabe Newell. Here I am showing it off the day I received it in July of 2012. It’s easily the coolest piece of video game memorabilia I own.

It really pains me to describe how hard I tried to leave teaching. It sounds so calloused, like I didn’t care about the kids. Like I was just in it for me and I wanted get out as quickly as possible. It’s obviously true that I wanted to change careers, but I’ve left out a lot of good times at school. The more time I spent teaching the more I loved it. I still think about my classes a lot. I go over conversations we had. I kick myself over all the mistakes I made in the classroom, especially early on. What I really hate is that I was part of a system where the teacher turnover rate is upwards of 40% year-to-year and I’m one of the 40%. I am comforted by the fact that I worked hard to make the school system better for the four years I was in it, but it’s hard not to think of ways I could have done more. I’ve held onto the dream that I’ll retire and go back to teaching at the end of my career. It only makes sense to bookend my career with teaching.

Before I get back to the main story, I want to get on my soapbox for a moment about teacher salaries. Holy cow, they should be tripled.

Tripling teacher pay would immediately make teaching a much more competitive career. Teachers could be held to much higher standards because they would know that there is a line of applicants waiting for their high paying jobs. You could raise the requirements for teacher training while still reducing attrition rates. The educational system would be transformed overnight, the beneficial effects of which would ripple outward through all aspects of the American system.

The further into my teaching career I got, the more I was on the fence about leaving. It was turning into a career I could enjoy long term. But the mix of long hours, stressful work environment, lack of respect, and very low pay compared to my equally educated peers pushed me over the edge. Tripling my compensation would have drastically changed the calculus in my mind and there’s a high likelihood I would have turned into a teacher for life.

My participation in Teach with Portals ramped up quickly after the letter. Over the next few months, I wound up writing a lot more lessons and creating a blog, Physics with Portals, where I shared video demonstrations of the physics lessons.

Despite all the effort of collecting copies of Portal, developing lessons, getting support from my administrators, and working with Valve, we still had IT problems getting Portal 2 installed on the school’s laptops. Numerous Internet and software admin policies frustrated my efforts to implement a whole class lesson with Portal 2. The school was subject to district policies, and district policies were slow to change. As a means of circumventing the issues and getting student feedback, I wound up bringing in my own desktop to school to do some one-on-one trial lessons with my physics students during lunch and after school. By the end of my third year of teaching, 10 months after first contacting Valve, I still had not yet actually taught physics with Portal to an entire classroom.

That summer, I learned about a physics teacher job opening at a nearby charter high school, LEAD Academy. This was intriguing because unlike the public school where I started my teaching career, the charter school had its own IT department and laptop policies. They also had a classroom cart of new MacBook Pros. In my interview with the principal, I explained everything that had happened so far with Portal and Valve and laid out my plans for teaching a semester of physics with the game. She was on-board and offered me the job. All of a sudden, all of pieces fell into place for a semester of actually teaching physics with Portal.

Valve invited me to visit their offices in Bellevue, Washington that summer too. I got to meet other educators teaching with Portal 2 and discuss the potential for video games in education with game designers at Valve. I also had a fateful meeting with Valve’s in-house videographers and documentarians, not realizing they were going to become a fixture in my classroom in the next school year.

In the main lobby of the Valve offices in July of 2012. I’m on the right. Leslie Redd and Yasser Malaika, a designer at Valve, are on the left.

When I returned home, I learned that they wanted to make a short documentary about my classroom. I shared the news with my new principal and we set the wheels in motion to allow a film crew to visit my physics classes. The pictures I’ve been sharing of my classroom all came from the documentary effort. I feel I need to spoil the ending of this part of the story. Before any of you reading this go off to try to find the documentary, you should know that it was never finished and nothing was ever released except for the few pictures and videos included here.

Leslie and Jeff Unay, one of the filmmakers at Valve I met, started flying out to Nashville to visit my classroom and meet my students in the fall of 2012. They decided to spotlight two students in the film. My class and my crazy ideas with Portal were to become something of a backdrop in showing what life is like for charter school students in inner-city Nashville. They collected about 80 hours of footage over three trips. In my estimation, only a third of the footage came from my classroom. The majority of the filming focused on the two spotlight students and the rest of the class. It’s easy to see why. These were really special kids. This school had lottery admissions meaning that any student in the district could apply. No academic requirements were necessary except the understanding that enrolled students were to always put forth 100% effort to their academics. The school didn’t care if applicants were smart - they just wanted them to always try their best.

Starring in a documentary was strange. I enjoyed the attention and the company. As a teacher, you spend so much time with kids that it can be a nice change of pace to have other adults in your classroom. I felt comfortable in front of the camera. My mom was a journalist and anchorwoman. I grew up around cameras. Talking to one felt natural, as did having them film my classroom. It was also a good exercise as a teacher reviewing footage of my techniques. In the video below, you can watch the raw footage from a classroom discussion I led about conservation of momentum.

The documentary also gave me a microphone to share my views on the universe. Here’s a short piece Jeff put together where I talk about my favorite hobby at that time, astrophotography.

I still wanted to be Carl Sagan, sharing a sense of wonder about the Universe.

I haven’t gone into much depth here about my classroom techniques and the physics lessons themselves because I wrote two pieces about the effort (and this story is already long enough!). The LEARNing Landscapes3 article describes the lessons themselves. The chapter I wrote for Teacher Pioneers4 gives my advice to teachers who want to try their own crazy lessons.

The Portal saga continued for a few months after the fall semester. Leslie and I gave a number of presentations at educational technology conferences with a few other teachers in the Teach with Portals effort. The communications about the documentary with Leslie and Jeff continued frequently at first but they cooled off and eventually stopped altogether. We at the school assumed that was because Valve was heads down working on the doc, but now we know it’s because the documentary was eventually canceled. I can only speculate as to exactly what happened, but from the outside it seems clear that Valve’s priorities shifted away from education. When I learned that Leslie lost her position at Valve sometime that spring, I knew that the documentary and the physics with Portal saga were over.

Behind all of this excitement with Valve and the documentary, I was desperate for a change. I was dating a girl who lived in Santa Cruz, California. I wanted to get out of Nashville. I spent most of my teaching career living with my college buddies. I was still going to the same parties and crawling the same bars on the weekends. I needed a change. I hadn’t let go of the idea of grad school. I had made a name for myself through the media coverage of the Teach with Portals effort and all the conferences. My name and my ideas showed up in all sorts of articles. I had teachers from all over the world reaching out to learn how they could apply similar teaching methods in their classrooms. I decided I wanted to study and build educational video games. I realized that my experience with Portal would create a convincing case in an application to a graduate programs in educational technology. I used the publicity we were getting to start networking with professors who were researching educational technologies. I made my second attempt at graduate school that year. I applied to the educational technology programs at my alma mater Vanderbilt, Arizona State, and UC Santa Cruz. I wound up getting accepted to ASU and UC Santa Cruz.

I believe I had already accepted the invitation to attend UC Santa Cruz when I would have another phone call with Leslie that would change my life.

I got a call from her when I was grocery shopping. This was after she had left Valve, probably around April of 2013. She spoke even more excitedly than usual. I had to stop shopping and walk over to a counter where there was a pen and some scrap paper. I started taking notes as she was telling me about this new business she was starting and wanted me to come with her. It was an educational technology company in Seattle. No name yet. She was the first employee, I would be the second. There was already enough angel funding for a year-ish of runway with a handful of employees. The business idea wasn’t clear, but it would have something to do with helping educators find useful teaching resources on the Internet. I don’t know if she used the phrase “iTunes for education” on the phone, but eventually that’s how we would explain it.

My First Startup Experience - LearnBIG

I had no experience in the business world. No clue what it meant to work any job besides teaching. But I realized how unique this opportunity was. Very few people get a chance to start a business about their passion. I recognized that this was the kind of opportunity I would have desperately wanted to find after going to grad school, so I figured why not skip grad school for now? Leslie’s passion was infectious, and after tangentially working with her for two years, I was excited to dive into a project with her full-time. Two days after the school year ended, I found myself on a flight to Seattle with no return ticket. Leslie let me crash in her family’s guest bedroom and we got to work.

This startup turned into LearnBIG. I started as the Director of Content. We quickly landed on the idea of a building a community of educators around online education. My immediate goals were to curate as much online educational content as possible as quickly as possible. This was the start of the summer, so we hired a team of interns to scour the Internet and build a comprehensive database. In the meantime, we hired a local contractor to build our website. We had big plans with discussion boards, playlists, rating systems, comments, and personalized suggestions. We wanted an experience that could support a vibrant, active community. Our early conversations about what success meant to us were phrased in terms of monthly active users. If we could tell a story around a growing community, more funding would surely follow. At some point, with enough users, we would even try to monetize (I actually don’t remember what our monetization plans were).

The original LearnBIG home page. I’ll take credit for the all caps “BIG” in our logo. I thought it made sense and I still think it looks good.

A few months later, we launched the website with a lot of fanfare and watched as our user engagement numbers were… in the single digits. Of our whole collection of educational resources, only two entries ever got a rating from users ever. It was an obvious failure from about the second day after launch. Basically by the end of the first week, we had basically abandoned the website and started a pivot to find a new product idea.

In hindsight, we made a lot of poor decisions. I feel conflicted about my role. I take some responsibility because I was there, but the fact of the matter is I didn’t know better. My whole business experience amounted to two months of scrambling in a startup and skimming The Lean Startup over a weekend. Our key mistake was simply that we invested a huge portion of our capital in an product without performing any actual market research. “If you build it, they will come” worked in Field of Dreams, but it doesn’t work in business. No one was asking for our product, so no one ever used it.

It was disappointing, but I wouldn’t trade this experience for the world. No better way to learn than trying and failing. And this is where I got my first taste of engineering.

A couple weeks into the process of curating the database of educational resources, a thought occurred to me - I was working on a website, but I had no idea how websites worked. I reminisced about my astronomy project where I simulated a star with C++. I had more free time now that I wasn’t teaching (yes, teacher’s hours are much worse than even the most devoted startup founder’s. Seriously, teachers need their salaries tripled), so I asked the engineers in the office for some direction on learning how to code. They pointed me to Think Python, a free textbook on the fundamentals of coding with Python. And I used our burgeoning database to find an MIT OpenCourseWare course on Python for complete beginners.

Learning how to code replaced my usual after work hobby of video games. I obsessed over the programming problems in the textbook and classes. My teacher instincts kicked in. Instead of solely consuming problem sets, I started to write my own challenges. I would riff off the problems by adding new twists. These usually took the form of, “we need to use thing A and thing B for this problem, but if I can figure out thing C, then I should be able to solve this other category of problems.” It started simple, like figuring out different math operators or having fun with recursion. But it quickly grew more complex to the point where I was building 2D physics simulators. Once I started to get a feel for programming, I branched out to C++ (again) and JavaScript. In those early days, I found it especially useful to compare paradigms and ideas between languages.

Simulating a 2D gravitational field with C++. The vectors represent the magnitude and direction of gravity at each location. The moving circles have mass, but I never got around to simulating their effect on one another. It’s a little buggy, but it gets the point across!

A month after I started coding again, I came across a problem at work I realized I could solve with code. I needed to scrape websites. There was data in hundreds of pages scattered across multiple websites we wanted and I desperately didn’t want to spend all day clicking, copying, and pasting. I sat down with the two engineers in the office and they helped me work out a script that successfully scraped websites and dropped the data into our database.

Deploying useful code came with a euphoria I hadn’t experienced before then. I loved studying physics back in college because it was fun solving problems, but this project made me realize how much more addicting it is to actually build solutions to problems. So, I kept coding and I haven’t stopped.

The two engineers there started giving me more challenging problems after that. Working with them is a key reason I am an engineer today. These two guys were (and still are) world-class software engineers and they took time during and after work to help me become a productive member of the team. They gave me real problems to solve and helped me learn how to think like an engineer to solve them. They pointed me to the resources software engineers use to solve problems - like searching Google effectively and reading documentation. They helped me think through problems methodically and plan out approaches. You couldn’t ask for a better environment to learn how to code. I feel incredibly fortunate to have had this experience. In a span of a few months, I went from complete novice to something resembling a junior engineer.

Learning how to code wasn’t without struggle. Our database of learning resources

at LearnBIG included a categorization system, with categories such as “K-6”,

“7-12”, “college”, “math”, “science”, “reading”, etc. The categories each

resource belonged to were stored as a single integer. I didn’t realize it at the

time, but it was a simple binary mask converted to an integer, where each bit

represented whether or not the resource belonged to that category. I wanted to

collect some statistics one weekend. I went to a nearby coffee shop and got

started with a Python script to unpack the categories. I remember writing a loop

that went over every resource’s category and every power of two up to

216, tracking whether or not the resource’s category was divisible by

that power of two. It took a long time to run, but it worked and I strutted into

the office Monday morning, excited to show off what I had accomplished over the

weekend. I showed the CTO my code and he laughed and asked if I had ever heard

of binary. He then walked over to a whiteboard, and wrote a two-line script that

did the exact same thing. He also pointed out my sin of individually querying

for each resource by ID in a loop instead of writing a SELECT * FROM query.

Later that year, I had a meeting with the CEO and CTO and officially became a full-time software engineer. It was a win-win - the company needed engineers more than a Director of Content after the pivot, and they knew how much I loved writing useful code.

In the meantime, LearnBIG pivoted to making corporate training material, which, granted, had an actual customer base, but it wasn’t an interesting problem to me. As should be evident by now, my interests were more in K-12 science and technology education. And at the same time, I was still dating a girl in Santa Cruz. I was flying down from Seattle to see her every two weeks. California was calling me and I wanted to spread my wings with my newfound coding skills. I started to look for job openings for junior software engineers in Silicon Valley.

My first interviews were a bust, with most interviewers admitting that they didn’t know how to evaluate my potential. I knew my unusual career path was going to be a tough sell so I kept applying. I soon reaped the benefits of networking, once again. Instead of going home for Thanksgiving, I celebrated it with my girlfriend at her friends’ house that year. She and her friends had attended an elite university. The father of one of her friends was (and still is) a well respected computer science professor at a top engineering program. Networking wasn’t my original plan for Thanksgiving, but when I learned who he was and that he was going to be joining us, I knew I had to meet him. We got to talking about Portal and LearnBIG and my new engineering career and goals. He was kind enough to offer to send my resume and some good words to folks that he knew in leadership positions at Udacity and Coursera. I jumped at the opportunity and emailed him my resume as soon as I was back at my laptop. Not long after, I got calls from recruiters.

This is another part of the story where I think I have an unfair advantage. I almost feel pampered. I had Leslie doting on me, then the LearnBIG engineers, and now I was able to get a stranger to speak on my behalf. It’s almost unfair but it goes to show how networking makes the world go round. Networking is what made my second attempt at grad school successful (even though I didn’t go). It’s what led me to Udacity. It’s how I eventually got to NASA, and, most recently, MIT.

The first company to reach out to me was Udacity. The recruiter told me that he had a position for something called a Content Developer (CD), which was an amalgamation of a teaching and engineering position. He explained that CDs were responsible for all aspects of designing, writing, building, and filming classes. I initially felt disappointed that this wasn’t strictly an engineering position as I had hoped to find, but the more I thought about it, the more it sounded perfect for me. I realized I would essentially get paid to continue learning how to code. And Udacity made a lot of classes with big companies like Google, which meant I would be working with and learning from the best software engineers. Being able to keep teaching was the cherry on top.

For the interview at Udacity’s Mountain View office, I had to present a 20 minute lesson on some programming topic. I decided to get creative and draw on my experiences teaching with Portal. At the time, I was focused on learning JavaScript and had recently struggled with the notion of a callback. My lesson was split in two parts. in the first, I would present a video with a demonstration in a custom Portal level where cubes represented functions being passed to functions. In the second part, I emulated the Udacity style of handwritten visuals and presented some questions to my interviewers.

An example of the original Udacity style of handwritten slides from one of my courses, Browser Rendering Optimization.

The interviewers and I clicked immediately. I immediately felt like we were on the same page. I held the skills, creativity, and passion required to push forward online classes. The interviewers and I became close colleagues and friends. I even wound up becoming roommates with one of them later on.

The interview wasn’t entirely smooth. At the time, Udacity had special catered lunches on Fridays, usually bringing in local restaurants to serve unusual cuisine. On the Friday of my interview, a French restaurant served sweet and savory crêpes. My interview started in the morning and went through lunch. My third interviewer, C, took me to the crêpe line. We jumped to the front, still chitchatting while we ordered our crêpes. I got to the end of the serving area and scooped some salad on my plate with a drizzle of balsamic vinaigrette. We returned to our conference room and continued the interview over lunch. I took a bite of my salad and immediately realized I had made a huge mistake. The salad on my plate was not, in fact, a salad - it was the plain arugula the caterers were using for the savory crêpes. Arugula is my favorite salad green, so no big deal there, but the dressing was not what I thought it was either. I had mistaken the caramel sauce for sweet crêpes for a vinaigrette and poured it all over my arugula.

So, there I was, interviewing for one of the best jobs I could ask for, one that felt like it was tailor made for me at that exact moment in my life, smiling and eating arugula with caramel sauce on it. It took effort to keep a straight face while answering all of C’s questions about my nascent technical background. I still cleaned my plate and left him none the wiser. We actually wound up being roommates in a four bedroom apartment in San Francisco a few years later (two other Udacians lived there, making it the unofficial Udacity apartment in SF). I shared this story with him and he had no idea about my salad mixup.

Udacity

I’m going to do a timejump in the story a little bit now. My career at Udacity was exciting and fun and I learned a lot and I loved my colleagues, but this is a period where things are more normal from a career and autobiography perspective. I’m going to be a little light on the storytelling and focus on an overview of the kinds of experiences that were formative for my current career. (For reference, I started working at Udacity around 2014. For the autobiography assignment, the earliest former colleagues I approached about getting feedback on my leadership skills were from Udacity. You’ll start to see their responses from here on below.)

While I was at Udacity, I worked alongside very creative and talented people to build online class experiences that make me proud. Making a class at Udacity required that people from multiple disciplines work together closely and communicate clearly. We had engineers and subject matter experts who would set curricula and goals, we had educators who would turn curricula into lesson plans with exercises and projects, and we had a video production team who would turn lesson plans into accessible content online. For most of the classes I made, I was both the teacher in the middle of the process and an engineer writing curricula.

I loved that I got paid to be as creative as I could be, all while using my love for teaching to spread my love for engineering.

Here are a few random sample videos from the classes I helped teach.

This redwood video was me trying to channel my inner Carl Sagan.

I think Mike and I got this on the second take. Also, I’m not sure why I wore the same shirt in both videos.

This was a fun style of video to make.

We often worked alongside experts from Google.

Maybe I should learn how to be a stuntman next?

I had to fully exercise the nascent leadership skills I developed way back when I was teaching. Organization, communication, and a clearly articulated shared team vision were essential for every class. I was pleased that one of my managers remembered that I was a “Direct, Solid Communicator” when asked about my strengths all these years later. They also hit on my attitude about collaboration: “Great teammate, always was a team player.”

I enjoyed building productive working relationships with people from all kinds of backgrounds. This was a startup too, so there was a constant looming pressure forcing us to work hard and be direct with one another. But it was teaching, which should be joyful for the students. It was important to me that we felt the same sense of joy in the office. The video team was an especially fun group to work with. In preparing for the autobiography, I was able to get feedback from a few of my former colleagues. One of the lead video production members had this to say about working with me.

You were a great colleague and I appreciated your humor and humanity. I can remember lots of times where you lightened a tense mood on set, listened to me or other colleagues vent, and helped troubleshoot issues that weren’t your problem. I appreciated you as a coworker and friend.

I took it upon myself to make sure each class was amazing. I was putting myself out there, creating content that would surely outlive anything else I had created up to that point. I wanted to set an example of good teamwork and positivity. That same video production colleague had this to say about working with me.

A project that Cameron was an instructor on was past deadline because of a lack of organization/time management of someone on my team, his colleague and my direct report. Instead of shrugging it off as not his problem or getting angry about it, Cameron was proactive and helped me work through the issue, doing everything he could to find a solution. It was a long time ago, but I’m pretty sure I called him 3x time on a holiday weekend to ask questions when I was in the office trying to find files!

I had a similar impression on my teaching colleagues. Directly or indirectly, we always collaborated on building classes. I was able to get feedback from one of my teacher colleagues all these years later. This person and I worked closely together on a number of courses.

I was consistently impressed at how fully Cameron dove into technologies that he didn’t yet understand, and how completely he learned them. I definitely appreciated collaborating with him on many courses because of how eager and motivated of a partner he was in the process.

That same passion worked against me sometimes. It makes me singleminded about pushing hard to produce what I perceive as the highest quality work, and in doing so it can create undue stress on the people around me. Once again, my video team colleague had this to say.

I dont [sic] remember too much detail, but there were a couple of times that Cameron got attached to an idea of how we could shoot something for one of his courses. When I told him it wasn’t possible due to budget constraints or timeline or whatever, he would sometimes continue to pursue the idea to the point where I became frustrated and needed to have a stern conversation with him and the rest of the course team to get them to move on and find a new solution. This wasn’t an issue unique to Cameron, to be fair, and I think was just a product of his passion for the material.

In total, I directed the development of 11 classes at Udacity ranging from web development to self-driving cars. Each class let me learn something new. It didn’t take long for me to realize that my job as a teacher meant I was actually a professional student. I realized I was getting more and more effective as an engineer. I started to love my job duties that required me to spend hours thinking about hard problems and writing code to solve them. At one point, I wanted to make an interactive exercise where students would make live changes to websites and get immediate feedback. I wrote a Chrome extension to grade them, which included the logic for both checking their work and generating useful feedback. For another class, I was dissatisfied with the options for providing useful feedback to students in the usual Udacity backend for grading quizzes. I wound up developing and sharing an entirely new feedback “engine” that was capable of running a robust set of tests against student code and returning specific feedback to guide student thinking to be able to solve the problem. It was a blast and I wanted to chase that feeling. About two years into my Udacity career, I made the switch to fulltime engineer.

A fun talk I gave about scaling online education in 2018.

I will admit that my career as a junior engineer at Udacity was productive but unremarkable from an outside perspective. I learned a lot and made some cool features for the website. It was primarily a time of learning and growth. I tried to glean as much wisdom and insight about engineering as I could from my colleagues.

Around this time, I started to get this itch. If I could go from zero to hero in web development in a matter of months, what else could I do? Could I revive my dream of space exploration? Why not?

I assumed grad school would be useful at some point, so I started going through online courses for what I assumed would be the baseline knowledge set for a grad student. On nights and weekends, I would casually watch math lectures, take notes, do problem sets, and take self-assessed quizzes. I knew this was practically useful, but successfully making the jump into space exploration would require networking and learning a lot more about the industry. An opportunity soon presented itself.

NASA Part 1 - Interesting Problems and Novel Solutions

Once again, through sheer luck, the person I was dating helped me make a connection. My girlfriend at the time (now my wife) has a brother who was in grad school studying aerospace engineering. Over a holiday, the topic of my itch to get into space exploration came up. He brought up the idea of talking to one of his classmates who was on a career track to work at NASA and needed some help with software. I actually turned him down at first.

“No thanks”, I stupidly said. “I’m going to stay focused on the online classes. I’m not ready to talk to him.”

It only took a day or two for me to realize how dumb I was. This was a golden opportunity to find a project that could lead to the space industry. I got back in touch with my now brother-in-law, and he connected me with his classmate, Matthew.

Matthew and I got along instantly. We were on the same page about our working relationship. I thought his research into human spaceflight operations was insanely interesting, and he thought my ability to build interfaces was insanely useful. We shook hands and agreed that I would write software for his cognitive engineering research on workloads for astronauts and flight controllers, and he would connect me with people who could help me start a real career in the space industry. To spoil the ending, our handshake was a wild success for both of us. He got a PhD on schedule, and I got a career at NASA. We’ve been working together at NASA for a few years now, having produced award-winning interfaces for decision making and analysis of spacewalks. Our team is on track for making software to support decision making when the next humans walk on the Moon.

When we shook hands, what I was really agreeing to was to give my nights and weekends over to the problem of understanding human spaceflight operations and writing software for addressing the perceived issues that Matthew wanted to address in his thesis. This meant a lot of conversations, studying, reading, and experimentation. I had to write a few novel algorithms for managing tasks and time constraints. We brainstormed and designed user interfaces together. I pushed code, he tested, and we deployed it to his on campus experiments where his classmates pretended to be astronauts and use the software to make decisions on Mars.

This research exposed me to a whole new world I wasn’t aware of - analog EVA testing (aka Extravehicular Activities aka spacewalks). These are simulated spacewalks that take place at various interesting locations on Earth that simulate some aspect of planetary or International Space Station (ISS) operations. There’s an underwater facility in the Florida Keys called NEEMO where astronauts and scientists live and work together, performing simulated spacewalks on coral reefs and scientific experiments in a habitat a lot like ISS. There’s the BASALT missions where astronauts and scientists go hike on lava flows around the world to better understand scientific sampling on planetary surfaces. There’s the NBL at NASA Johnson Space Center where crews perform simulated spacewalks on a to-scale replica of ISS. What Matthew realized is that these facilities and experiments were perfect research opportunities for testing his ideas about reducing the cognitive workload required for decision making during EVAs. As such, our goal became to integrate our software at one of these test sites and demonstrate its utility. I got a chance to visit some of these locations, deploy my software, and generally learn how I could best support human spaceflight operations.

Me at the foot of a lava flow at Craters of the Moon National Park as part of BASALT in 2016. Behind me, a simulated astronaut (with the antennas) looks for scientific samples while the other hiker simulates the kind of tool and sample storage support you would get from a rover.

There were sleepless nights and frantic rushes to test and deploy software. Each field deployment was an opportunity to demonstrate some unique value or test some interesting tech idea. We called our software Marvin, after Marvin the Paranoid Android from Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. We wanted it to reduce the mental math required to monitor the temporal constraints inherent in doing dangerous jobs while being kept alive by portable life support systems. The most important number it produced was the timeline margin, or the amount of time between the predicted end of the EVA and when life support would run out. This meant we needed a way to collect information about the crew’s progress during the EVA in as unobtrusive way as possible. Our interface was designed to be very simple - just checkboxes and timers that made sense at a glance. If you’re interested in learning more, check out the blog posts I wrote about Marvin here, here and here and Matthew’s thesis5.

After he graduated with his PhD, Matthew got a job at NASA as a research engineer for human spaceflight, and I followed behind him a few months later.

NASA Part 2 - Realizing (the Problem) Space is Bigger

Much like I did in the Udacity section above, I’m going to jump around a bit to talk about the impact of my time at NASA. I’ve spent most of it working on two software projects - one that focuses on bolstering insights into EVAs, the other that focuses on helping image analysts share their findings.

As a colleague, I got similar feedback about my strengths and weaknesses from the folks I work with at NASA. In my survey, I heard that “Your enthusiasm and genuine personality is awesome to be around.” Someone else said that I am a “Self-starter, highly skilled, interested in learning, [Cameron] can pull back from ‘interesting’ approaches to favor practical approaches, [and is] able to lead by example.” My teaching background also came up as a positive. The same person said that I am “Super helpful! Open to teaching team mates (especially me) in the name of project success.”

What I see as a key differentiator between Udacity and NASA is that I hit my limit in my ability to multitask, and that led to some downstream effects that negatively impacted my colleagues.

We were working on a side project for a NASA analog a few years ago (pre COVID) and we had started to converge on some expected functionality and I thought we had a tangible path forward. But it wasn’t until later that I learned that his other project needed a lot of his attention and I wasn’t aware he was as oversubscribed as he was. Being more honest of availability and anticipated work hours would help keep the expectations reasonable and achievable. Fortunately, the analog never ended up happening so we never felt the big crunch that would’ve likely been experienced.

An intern I mentored said something similar.

I sometimes had trouble scheduling meetings and communicating with Cameron - this is 90% down to circumstances (remote work, grad school, me also being quite bad at this), but Cameron can still be more mindful and creative about how to be present despite circumstances

This is a weakness I’ve worked hard to address. I don’t like the feeling of letting others down. As we’ll see later when I get into my career as a grad student, this is a blocker I’m still addressing.

Another colleague gave me some very insightful feedback about my growth as a leader and how I will need to adapt to managerial positions in the future.

Cameron is an excellent leader already and shows no indication of slowing in his growth as a leader. Currently, Cameron works with people as good or less skilled than he is, and as discussed above is able to perform at a very high level in that role. All technical leaders hit a point where they are less hands-on and members of their team are approaching problems differently than the leader would, culminating in a situation where the leader is hands-off but responsible for what is being produced by their team—who are approaching problems differently than the leader would. Job satisfaction also comes less regularly when you’re a hands-off leader. One mitigating approach to counteract this is for the leader to hire team personnel who are better than they are at technical approach, putting themselves into an “enabler of excellent work” role. This is a difficult transition for every technical leader and will be especially difficult for Cameron given his very high level of technical knowledge and experience. He’ll have to search for a long time to find team members more skilled than he is.

The intern had similar points about my continued tendency to teach: “effective teacher, gives useful feedback, respectfully defends technical opinions, pleasant person w/ positive attitude.”

I wish I could go into more of the specifics about my career at NASA, but none of the work I’ve done is public. I hope some of it will be public soon, because I’ve been lucky to lead some projects that have made some really amazing software interfaces for EVAs with which I’m sure the general public would love playing. In short, I’ve been lucky to architect one award-winning project, and another that’s now being used for testing Artemis launches. My colleagues are incredibly bright and fun to work with, and I couldn’t ask for a more interesting or motivating problem space.

It’s probably clear by now that I like looking for opportunities. I’m still testing my theory, but I think I found one in the world of EVAs. I’ll take a quick aside to give some background about human spaceflight operations, which will motivate why I made my next set of career choices.

Clocks dominate EVAs. Temporal constraints exist between every activity the crew perform. It could be that certain tasks must be performed within some amount of time of one another. Some tasks are completed on repeating intervals throughout EVAs. Everyone has an eye on how quickly consumables, like water and oxygen, are being depleted as they give the most accurate insight into the total length of the EVA. Everyone is doing mental math to figure out exactly when events in the future will happen. Meanwhile, flight controllers are planning and replanning for potential future events. When something inevitably goes wrong (which is usually something small, like a bolt that won’t screw in or a snagged cable), it has downstream effects that must be accounted for. All this is to say that there’s a lot of temporal reasoning going on during an EVA, but there are few, if any, advanced tools (aka computers) doing the math for anyone5.

Preparations for Artemis are well underway. Mars will come next. Current human spaceflight operations depend on human computers, but time delays will necessitate moving some of that temporal reasoning and planning capabilities in situ to the planetary surfaces that astronauts will be exploring. I love this problem. What a cool application of math and logic - keeping people alive, safe, and productive as they extend humanity’s reach in the solar system.

I knew I lacked the necessary background to build the advanced decision support systems for exploration. I had not given up the dream of grad school. Through some connections at work, I was able to get in touch with some professors in programs that work on challenges in human spaceflight. Knowing it was a long shot because my academic background had not improved in the intervening decade since college, I applied to MIT AeroAstro. And I was rejected. It stung at first but it faded quickly. I knew that receiving a “no” from a grad school application only meant “not this year.”

Meanwhile, my then-girlfriend and I were due for a move (she’s in a career where people frequently move for the first 10 years or so). She was accepted to a program here in Massachusetts, so we found ourselves planning for a move to Cambridge. I had a vague notion that lots of universities have programs for local professionals who want to take a class or two. A few minutes of research uncovered that MIT has the Advanced Study Program (ASP). It seemed like a great fit. I was close enough to campus to take classes. Almost any class in the course catalog was available, so long as I could make a case that I had the listed prerequisites. I found Principles of Autonomy and Decision Making (16.413), which seemed to speak directly to the kinds of problems and advanced decision making we’ll face on planetary surfaces. Two months after getting a rejection letter, I was submitting another application to another program at MIT. This time, I was accepted!

Beginnings as a Researcher

I wrote about my experience in 16.413 previously. In short, I loved the class. There were clear applications of the model-based approaches to decision making and temporal reasoning with my work at NASA. This class felt right. These were the skills I wanted to integrate into my career. So, just as I had done before with Matthew to get into NASA, and with Leslie to turn Portal 2 into a teaching tool, I networked with the professor of 16.413, Brian Williams. I wanted to be honest with him to try to find a way to turn the skills we were learning in class into a new career. I grabbed him after class one day and gave him a rundown of my background.

“I am interested in getting a masters,” I explained. “This class is amazing, and I see a huge amount of potential with the kind of decision making we’re working on at NASA. I’d love to get involved with the lab.”

He was supportive and invited me to join the lab’s group meetings. Of course, I accepted.

Over the course of the next year, I got to know Brian and the other members in the group better. At later group meetings, I presented on my work with EVAs and described how I had been implementing some of the temporal reasoning algorithms we were learning in class in the decision support systems at work. I signed up to take the follow up class to 16.413, 16.412 Cognitive Robotics, in the spring.

With more conviction about my future as a researcher and practitioner of model-based automous systems, I applied to MIT AeroAstro again. Brian helped with my application, especially with respect to building a case that (a) there was a need in the field of planning for the research I wanted to perform and (b) my unusual career thus far made me a strong researcher.

I was rejected again. I will never know for sure why I wasn’t accepted, but it isn’t hard to imagine that my poor undergraduate grades, unconventional background, and lack of concrete research experience in the field of autonomy weakened my application.